Features

Mills

Sawmilling

Maritime machines: J.D. Irving fully automates the tie line

J.D. Irving’s Veneer Sawmill in Saint-Léonard, N.B., recently installed two robots on the tie line that are performing what was once a labour-intensive and repetitive task at the mill. Now, the job that was once the most difficult is the most sought-after: robot operator.

May 26, 2022 By Maria Church

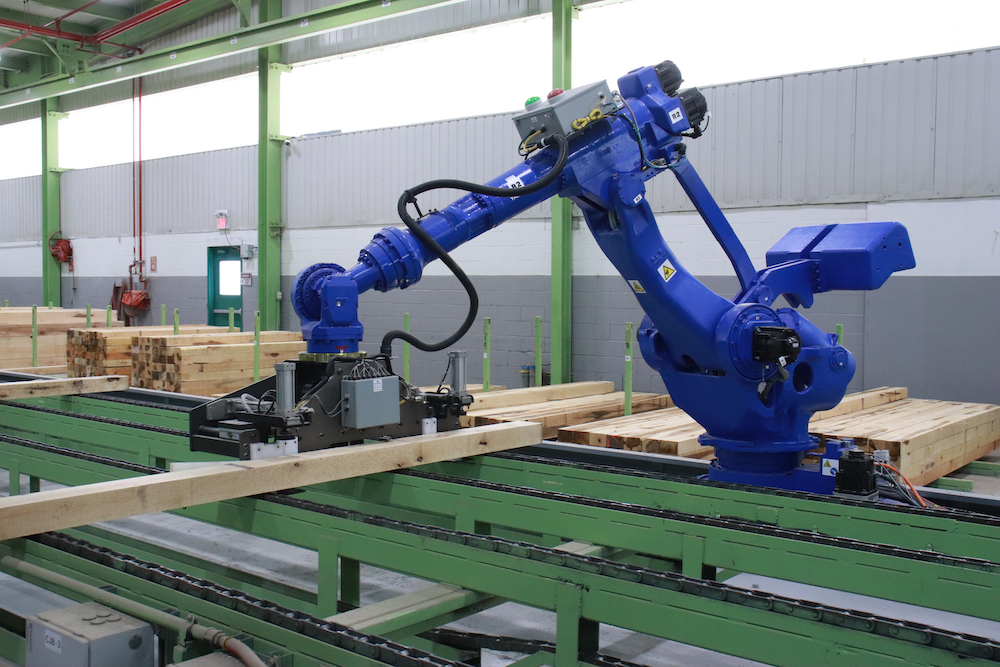

Each of J.D. Irving’s robotic projects were managed in-house by their team, resulting in new lessons learned about their own capabilities and what it takes to make robots work in a sawmill environment. Photos courtesy J.D. Irving.

Each of J.D. Irving’s robotic projects were managed in-house by their team, resulting in new lessons learned about their own capabilities and what it takes to make robots work in a sawmill environment. Photos courtesy J.D. Irving. Modern sawmills in Canada are teeming with sophisticated machinery producing far more lumber, far faster and more efficiently than ever before. Yet, modern mill or not, they all have recruiting challenges.

At J.D. Irving’s (JDI) Veneer Sawmill in Saint-Léonard, N.B., one such challenge was the tie line where the mill sorts 19 of its largest hardwood products, including rail ties and pallet components.

Mill staff would either hand pile smaller product or operate a vacuum system to lift the heavier ties and sort them in 20 odd bins before a forklift carries them off to their next destination. The job was labour-intensive and repetitive, which carries a high ergonomic risk.

Today, the mill has two permanent, tough-as-nails labourers filling that job – Buckdjeuve (Jackalope, in English) and Tie-Rex. These are the names mill staff have affectionately given the new articulating robots working on the Veneer Sawmill tie line.

Rather ionically, the robots are an investment JDI made specifically for its people. A job that was once the most difficult is now among the most sought after: robot operator.

Jody Gallant, business improvement manager with JDI’s hardwood and pine division, led the charge to install the robots at Veneer. He makes it clear to all staff that the robots are there to perform the roles that are toughest to fill.

“I’ve worked in the sawmills for quite a number of years, specifically in the Doaktown mill, and there are a lot of good workers and the last thing we want to do is demotivate people,” Gallant says. “We know the labour market is changing and we know we have less people applying. So let’s make the hard jobs go away and focus on the value-added jobs and jobs that people enjoy doing, that they get up and are excited to come to work for.”

JDI has invested in robots to perform labour-intensive tasks that are difficult to recruit for.

Robotic ride

The robots are indeed a treat to watch. It’s more like peeking in on an auto assembly line than a sawmill. A vision system watching the tie line tell the robots which items are located where. As products are conveyed down, the robots travel on their own parallel tracks, identifying an item, scooping it up, rotating 180 degrees, and depositing it in its bin.

Supplied by Yaskawa, the robots were a central component of a $1-million in-house lumber handling modernization project at the hardwood mill that also involved a new Samuel strapping machine.

Susan Coulombe, JDI’s general manager of hardwood and pine within their sawmills division, says the bulk of the budget was not spent on the robots, but rather the lumber handling configuration needed to allow the robots to function correctly. That configuration is key to the robots’ success.

“The one theme through every project we’ve done with robotics is that the robot will do exactly what you tell it to do – that part is the easiest. Making sure the piece is where it’s supposed to be is the biggest challenge. If you tell the robot the piece is going to be at position 140, it needs to be at position 140. The robot is not going to go, ‘oh, you mean 130?’” Coulombe says.

This tie-line project is the latest iteration of JDI’s robot journey. That journey began with their Doaktown, N.B., sawmill where they installed a robot on the paint line in 2016. Two years later, they put a higher-speed robot on Doaktown’s resaw system. In 2020, as part of a planer upgrade in JDI’s pine mill in Dixfield, Maine, an articulating robot was installed to stack two-foot blocks.

“We always learn things and we’re always pushing ourselves. After we had success on that scale, we had a look around and thought, where’s the next opportunity for this. This application in Veneer was ideal,” Coulombe says.

Each of the robotic projects have been managed in-house by the JDI team, from designing to spec’ing equipment, building and start-up. “When you’ve got that many people with a stake it in, it’s hard to fail,” Gallant says.

Robot supplier Yaskawa used a 3D model of Veneer Sawmill’s tie line to provide sample cycle times. During start-up, the robots were found to be capable of double their required speed.

Weighty undertaking

Veneer’s project was unique in its scale. The ties can be up to 300 pounds and 12-feet long. The length specifically presented leverage challenges and required large robots capable of handling more than 800 pounds, Gallant says. Speed was less of a concern.

“There’s about one tie per log, roughly. The mill consumes about 1,500 logs per shift, so the maximum rate we produce these ties is around two and a half blocks a minute. So, the rate is not that high,” he says.

Yaskawa was able to 3D model the line to do sample cycle times. Each robot was estimated to pile two blocks a minute, giving an overall of four blocks a minute. During start-up, the robots were each able to surpass four per minute – double what was required.

“Robots have a long history in the automotive industry. It’s really not the robots that are cutting edge, it’s more the application,” Gallant says.

He sees two reasons why sawmills have been slow to adopt robots. The first is a perception of high costs, despite costs coming down significantly in the past several years. The second is programming language. Robots typically are programmed using a language that requires specialized training. Yaskawa’s robots are programmed with the same language used in the sawmill’s PLCs.

“That really reduces the learning curve. Our in-house instrumentation department had, I think, two hours of training and now they’re maintaining the robots,” Gallant says.

After the initial expense, upkeep costs for the robots are minimal, involving regular inspections and cleaning.

“If you follow their design recommendations, they expect a 25-year lifecycle for these robots with minimal maintenance. It’s a pretty easy investment – there aren’t big rebuilds after a few years. But it all depends on how well you take care of it.”

Modern mill

Veneer Sawmill employs around 75 staff on two shifts. The 40 million-bdft mill batch runs three species – maple, soft maple and birch.

Twelve-foot logs are treated first to Nicholson debarkers before running through one of two Cleereman carriages. The mill runs a PHL merry-go-round resaw and bull edger before a Comact TrimExpert scanner at the trimmer. About 80 per cent of Veneer’s product is sold green rough, but the other 20 per cent is sent to J.D. Irving’s drying operation in Clair, N.B., about an hour’s drive east of the mill.

The hardwood mill has more than 200 products, most of which are handled by a PHL 60-bin drop sorter and PHL stacker, but the tie line has always been a manual process.

The robots started up piling the tie line full-time in February. Phase 2 will be underway shortly to adding stickering capabilities.

Coulombe says the return on investment for the Veneer project is close to three years, but the strategy behind it lies the workforce.

“With labour being our No. 1 challenge, we need to find ways to make our places of work attractive to people. It’s been a great team project,” she says.

More robots are likely in JDI’s future as the team gets familiar with their capabilities and what it takes to make them work. And both Gallant and Coulombe are expecting to see robots crop up in mills across Canada sooner rather than later.

“I think there is a preconceived notion that robots don’t belong in sawmills, and I think that’s slowly going away,” Gallant says. “There are tasks that are non-value added, that are repetitive, and it’s easy for robots to do.”

Print this page