Features

Forestry Management

Harvesting

Revisiting tenure: Managing competitive forests to supply a competitive industry

May 31, 2018 - Canada has 397 million hectares (ha) of forested land. Approximately 190 million (48 per cent) is considered to be suitable for long-term sustainable management for the production of timber, while 165 million ha (87 per cent) of that forest is publicly owned and managed under the authority of the provincial governments. Another 20 million ha (10 per cent) are private woodlots owned by some 450,000 rural families across Canada, with the average size 40 ha.

May 31, 2018 By Tony Rotherham and Ken Armson

The balance, five million ha (3 per cent) is in large blocks of private forest land owned by a mix of private investors, forest products companies and pension funds.

The Allowable Annual Cut (AAC) is approximately 230 million m3 (165 million m3 of conifer and 65 million m3 of hardwood). This article, for the most part, excludes B.C. The structure and supply chain of the industry in B.C. has been different, due largely to tree size.

From the beginning, the Canadian forest products industry has been driven by export markets. Napoleon’s 1805 blockade of the Baltic countries sparked exports to Britain. During the 1880s the sawmilling industry responded to market opportunities in the U.S. to support the rapid growth of towns and cities there. In 1911 the U.S. government lifted tariffs on the import of paper and opened the door to the establishment of a robust pulp and paper industry in Canada. The industry has been through several significant structural changes in products and the supply chain since those early days. The pulp and paper industry used roundwood almost exclusively until 1960, when the use of sawmill chips started to replace the traditional use of four- and eight-foot logs.

But in the provinces from Alberta eastward to Newfoundland and Labrador, it was not until 1985 that most of the wood harvested was delivered as sawlogs to sawmills instead of as pulpwood to the pulp and paper mills.

This transformation from the exclusive use of roundwood by pulp and paper mills to increasing use of sawmill residues brought benefits to the pulp and paper industry and the sale of chips brought a new revenue stream to the sawmills and enabled the growth of the lumber industry. The increasing use of sawmill residues by the pulp and paper industry resulted in a significant improvement in the utilization of harvested logs. Beehive burners disappeared.

Between 2000 and the present there has been a change in the demand for forest products in the global marketplace. The demand for paper products, particularly newsprint has declined, and demand for lumber has increased.

Fifty-eight of Canada’s 141 pulp and paper mills have closed since 2000. Companies vacated many large forest management licences previously managed to provide wood for those mills. New forest products industries have been sought to undertake management of these lands and to support the economies of the forest-dependent resource communities. Two positive factors are:

- a new and growing market for wood-based bio-products including wood pellets for energy generation, primarily to replace coal and oil, and

- the manufacture of timber panels and engineered wood beams such as Cross Laminated Timber (CLT), Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) and a variety of wood-based panels.

The significance of these changes is the increasing dominance of the solid wood sector. The changes in the proportions of P&P and solid wood products are shown in Figure 2.

All sectors of our forest products industry declined during the recent recession (20062011). Specific high-impact factors were: the collapse of the American housing industry and the explosion of internet communications. The harvest levels fell from over 200 million m3 in 2005 to 116 million m3 in 2009.

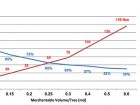

Tree size is largely irrelevant to the pulp and paper industry. Logs large and small go into the chipper. But the size and quality of logs is important for manufacturing lumber and wood-based panels. Tree size is also the single most influential factor in determining harvest costs and production of lumber. (Figure 3.) The vast majority of logs are now delivered to sawmills. We should start to direct our forest management and silviculture to produce large diameter sawlogs — not small diameter pulpwood.

Silvicultural practices that control stand density to promote diameter growth and log quality are needed to grow timber for the solid wood industry. However, the time required to benefit from the results of silvicultural treatments to improve tree size and quality is longer than the term of the tenure contract for most provincial licences signed with forest companies. In both volume and area agreements, some companies can look back on many decades of management and operations on their licence area, but few can look ahead with confidence to the future 50 years or more of wood supply from the same area. There are two reasons for this: markets change/companies rise and fall; and governments change the terms of the agreements.

But the forest-dependent communities remain. Therefore — except for the post-harvest regeneration of their cut-over forest lands — the licencees have had no incentive to invest in silvicultural treatments to improve tree size and quality.

It has long been recognized by foresters that on any large area of managed forest there will be areas that have a combination of productive soils, good topography and access. These are referred to as “Prime Sites” and should be the focus for silvicultural treatments to improve tree growth, size and quality. In Canada, there are two basic forms of tenure on provincial forest lands: volume agreements and area agreements. (Figure 1.)

Volume agreements: The provincial forest manager is responsible for the long-term forest management plan and allocation of areas for annual harvesting operations. Post-harvest regeneration may be the responsibility of the provincial manager or the company that harvested the timber. There is little to no incentive to promote growth or enhance tree quality.

Area agreements: These agreements are traditionally signed with a single forest products company. The company is responsible for the preparation of a long-term forest management plan, subject to approval by the province. The company is also responsible for all forest operations including post-harvest regeneration. While the licence may be for at least 25 years and renewable there is little evidence that companies managing area agreements have seen any incentive for long-term investment in silvicultural treatments to improve tree growth and quality.

At a conference in Quebec City several years ago Michel Vincent, economist with the Quebec Forest Industry Council, emphasized the difference between “profitable” and “competitive”.

Profitable is an accounting term. It reflects the short-term accounting difference between revenues and costs; it is easily measured.

Competitive is a term used by economists. It encompasses the long-term relationships between suppliers and customers and reflects the combination of raw materials, labour, international trade, capital and the ability to maintain modern productive mills; it is difficult to measure. Competitiveness results in long-term profitability.

It was agreed that a competitive forest is the foundation of a competitive industry. Resource-dependent communities also depend on the quality of the forest.

We believe that provincial forest management policy should focus on developing and maintaining our managed forests to provide a competitive forest to support a competitive industry and prosperous communities. What are the characteristics of a competitive forest that will provide a combination of long-term and renewable economic, social and environmental benefits?

- A healthy, productive, resilient and biodiverse forest.

- A focus on improving timber size and quality appropriate to the needs of the industry and the marketplace for its products into the future.

- Management that ensures the conservation and maintenance of wildlife and habitats, water quality and of other values such as landscape aesthetics and forest recreation.

- A focus on the provision of long-term involvement and economic benefits to the forest-dependent communities, including First Nations.

There are several ways in which a competitive forest may be established and managed.

Tenure and governance are key aspects of this. The form of tenure should be a secure, long-term area agreement signed with a forest licence holder rooted in the communities and companies surrounded by and dependent on the forest they manage.

The form of management responsibility will depend on the location of the forest, the types of communities and forest industries involved and the nature of the forest itself — flexibility is required. Ideally, the forest management licence holder will be a company with a board of directors that includes representatives from local communities, First Nations, forest industry and other forest-based enterprises. In several provinces there is a move towards such arrangements. The objective is the provision of secure tenure to provide the incentive to support long-term planning, the identification of prime sites and investment in silvicultural treatments to promote the improvement of tree growth, size and quality.

There is increasing pressure from urban society and special interests to set forest land aside in protected status and “protect” it from management and harvesting. There is also increasing public demand for companies to have “social licence” in order to produce social and economic benefits from the management of our natural resources. In some provinces a proposal to replace volume agreements (managed by a government agency) with area agreements (managed by a forest products company) has been criticised as the “privatization” of public forests. Perhaps if forest tenure agreements were signed with forest management organizations — that includes municipalities, First Nations communities as well as forest companies and other forest-based enterprises — the establishment of a new type of area agreement might be met with greater acceptance by the general public and support from forest-dependent communities.

Tony Rotherham (RPF B.C. and Ont. (ret’d)) has worked on woodlands operations in B.C., Ontario, and Quebec as well as in Kenya and Iran. He worked for the CPPA (now FPAC) in the Woodlands Section for 21 years until 2001 and since then as a consultant, largely on private forest land policy.

Ken Armson (Order of Canada, RPF (ret’d)) was a professor of forestry at the University of Toronto for 26 years and then with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources for 11 years. He has been involved with silivicultural practices primarily related to regeneration on both Crown and private lands across Canada.

Print this page