Industry News

News

Size Matters

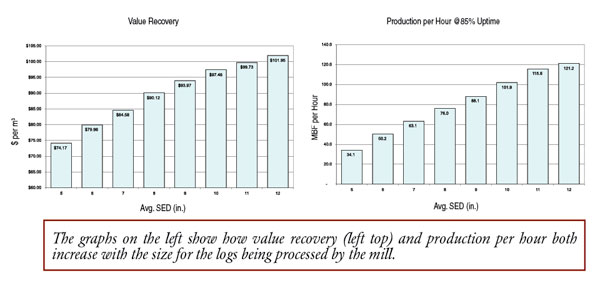

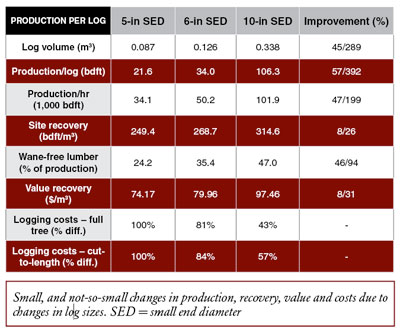

Tell your girlfriend what you want, but in the world of sawmilling and log harvesting, size really does matter. Sawmilling is a lineal process. Think of your average mill as a solid tube of wood starting from the log infeed and debarkers, and running all the way through the primary breakdown line where the log is first turned into something resembling lumber. However long that line is, that’s all the log you’ll fit – period. All a modern mill can do to boost the volume going through, is move that tube faster (boost processing speed or close the gap between logs) or find a fatter tube to run through the mill in the first place. Double the diameter of the log from 5 inches to 10 inches and you’re not “just” doubling the lumber coming out of that log. As the “Production per log” table on page 20 shows, you’re seeing a five-fold increase in lumber production from that 16-ft. log! Even many who think they get the impact of log size on sawmill production are stunned by that magnitude.

December 1, 2011 By Brad Turner & Scott Jamieson

Tell your girlfriend what you want

Tell your girlfriend what you wantSimilarly in the woods, regardless of how fat the tree is, it’ll take roughly the same time to cut and process. This reality means changes in log sizes will dramatically impact the money you spend getting logs to the millyard, as made crystal clear by a sliding harvesting productivity scale provided to the authors by FPInnovations – Feric Division. A slick tool tracking relative logging costs by tree size in both full tree and cut-to-length simulations, and based on real Feric field data, it came to us via Jean-Francois Gingras with the caveat that it is a theoretical tool only. Still, the results illuminate.

Start with trees averaging 0.2 m3/tree as our baseline, a common benefit of working in parts of B.C., Alberta, Ontario, and rare corners of the Maritimes. Now travel to parts of Quebec, New Brunswick, or northern Ontario, and find yourself struggling through bush averaging 0.1 m3/tree. Assuming you’re geared up for small wood and know what you’re doing, your cost of getting processed trees to roadside has leapt by 55% in a full tree system and over 35% in a well-oiled CTL system.

Most in the industry might feel they know all this. Still, for those new to the game, and even for the rest of us, it’s important for several reasons to occasionally take a closer look at the relationship between log size and productivity, volume recovery, and product value.

Apples to Oranges

For starters, there’s everyone’s favourite topic – the on-again softwood lumber dispute. When it comes to cross-border log cost comparisons, log size is often an under-appreciated factor. Leaving currency, distance to market, and Crown forest management responsibilities aside for a moment, not all sawlogs are created equal. Simply put, what passes for a sawlog in Chibougamau, Que., bears no resemblance at all to the sawlogs arriving at a typical Southern Yellow Pine (SYP) sawmill in Alabama, which may again differ from the Spruce-Pine-Fir (SPF) logs arriving at a northern Interior mill in B.C. Each brings a mix of logging costs, productivity and potential product value that affects its true market value.

Take the small end diameter (SED) 16-ft. sawlog examples we’ve used to run the simulations for this article. Start with a “typical” SYP mill SED of 9 inches, move to today’s average of a 7-inch SED at a B.C. central interior canter line, and then sadly come to rest at an average SED of 5 inches you might expect in a northern Quebec dimension mill. Never mind that the latter two originate some 1,000 kilometres or more from the market; intuitively we know we’d never pay the same cubic metre charge for these logs. And with good reason. As the comparative Production per Log chart shows, even an inch difference in SED can severely impact a mill’s productivity and profitability, and thus what it can afford to pay for its logs.

These comparisons are also key to loggers, especially private woodlot contractors, bidding on potential contracts. The simulations may be theoretical, but the percentage differences are real enough to consider closely when looking at a stand of small wood. Also, as the industry emerges from the current doldrums, and entrepreneurs from central Newfoundland to northeastern New Brunswick and the central interior look at suddenly-available small log supplies, grasping these factors will be central to any business plan.

Finally, and our main reason for this look at the impact of log size, is the changing face of the Canadian forest products sector in many regions. As the forest industry re-tools and re-invents, many regions have lost or may soon lose their historical pulp wood clients. This is especially true in Atlantic Canada (and border states), parts of Quebec and Ontario, and Saskatchewan. So if your clients for your logs, big and small, are now principally solid wood players with perhaps an emerging bioenergy sector on the side, it’s perhaps worth considering who we’re now growing trees for and who we’re likely to be selling them to in the coming decades. Private landowners may have more latitude on this front, but Crown land managers may also want to consider how we manage (spacing, pre-commercial and commercial thinning) and when we harvest our future resource.

All food for thought as you look over these comparisons and charts relating log size to sawmill production, lumber recovery, product mix, product value, and relative logging costs to roadside.

Sizing the Costs

From the more detailed results supplied by HALCO’s SAWSIM simulations, CWP Magazine has extracted a few comparisons to make its own chart (page 20). We’re looking at the changes caused by a relatively small jump in log size that might come from small changes in forest management regimes or harvest timing (5 to 6-in. SED), as well as the big leap to a 10-in. SED you may see from comparing regions or the very long-term impact (80 plus years) from an investment in intensive forest management over letting Mother Nature have

her way.

Starting with the costs of getting the wood to roadside, we’ve made some ballpark percentage comparisons based on log volume, where trees yielding on average those 5-inch SED logs represent the baseline roadside cost at 100%. In that case, that 1-inch difference in tree size may shave 16 to 19% off your cut-to-length (CTL) or full-tree (FT) logging costs. Logging trees yielding on average 10-inch SED logs on the other hand will cut logging costs almost in half.

Once the resulting stems hit the mill deck, the difference in production, unit costs, and sawmill profitability grows. Log volume (or how much solid wood your sawline can “hold” at any given time) jumps a whopping 45% with an extra inch SED, and a staggering 290% by doubling SED to 10 inches. Gains in lumber production per log are even more pronounced thanks to the nature of getting square products from a round raw material – 57% more lumber per log with a 1-in. gain in SED, or almost 400% with a 10-in. log. Productivity per hour climbs as a result, by 47% for a 6-in. log and 200% for a 10-in. log (although the logs contain much more volume per lineal foot, line speed must slow down to allow the cutting tools to handle the “bigger bite”).

One important aspect of today’s markets is the percentage of wane-free, or square-edge lumber, a mill makes, as these are the products in demand by the big box hardware stores. The percentage of wane-free lumber climbs dramatically with the move from 5- to 6-in. SED (by 46%), as well as by the move to 10-in. SED (94%). Finally, value recovery, the total value recovered per cubic metre log volume processed, also climbs with log size, from $74.17 for products made from that 16-ft., 5-in. SED log to almost $80 (8%) from the 6-in. SED log and almost $98 (31%) from a 10-in. piece. Value gains come from higher cubic recovery, a greater percentage of wane-free lumber, and a greater percentage of wides produced (2x10s).

Put it together, and there’s little doubt a truck load of 6-in. SED sawlogs is worth more to the average sawmiller than that same volume of 5-in. SED logs – more than many might assume. If a delay in harvest or investment in intensive silviculture means producing a diet of average 6-in. SED instead of 5-in. SED logs, your logging costs could drop 19% (a huge difference in today’s world), your productivity per hour climbs 47%, your recovery increases by 8%, and your percentage of more marketable four-square lumber grows by 46%. Not a bad return on a one-inch gain.

Behind the numbers

The charts and spreadsheets on which this article is based came to us from HALCO Software Systems’ well-known SAWSIM sawmill simulation software. As always with such simulations, we’ve made a few assumptions.

First, HALCO weighted samples of “typical” SPF stems to follow alternative size distribution curves, and bucked them to 16 feet in a cut-to-length operation. Through this process, they generated alternative mill log supplies that had reasonable distribution curves, and average SEDs from 5 to 12 inches, in one-inch increments.

They then processed the alternative supplies in a “state-of-the art” two-line sawmill. The mill was configured with either one or two board edgers and sort lines, as it would be reasonably configured for the different log sizes. The mill produced 2×4 through 2×10, plus 1×4 and 1×6. Lumber prices were 10-year average values for Western SPF, taken from Random Lengths, with the addition of a “Home Center” grade product for the 2-inch sizes, with a reasonable premium assumed. Of course, these Home Center products are a significant factor for many mills today, and for this reason one of the key results we charted was the per cent wane-free lumber recovery, as this is important for recovery of these Home Center products (most are required to be wane-free, or near wane-free).

Logging costs are a trickier matter when trying to tie them to the various products making their way to the mill. When asked about the impact of log size on harvesting costs and final product costs, one western HALCO client commented, “I’d like to see a mill with an average SED of 12 inches – that would be something! Most of our mills are in the 5 to 7-inch SED range, usually around 6 inches give or take a little. Harvesting is like sawmilling, where any machine that handles wood lineally is impacted big time by the volume per piece. Processing is the biggest impact, but falling can also be significant. Skidding with a grapple is less impacted – as is loading, as the grapples just handle more pieces per cycle (but smaller usually means shorter as well, so there is still some volume impact).”

This same solid wood products producer noted that his operations supervisor ball-parked a 25% decrease in harvesting costs by going from a 5- to 12-in. average logs. If they were looking at about $20/m3 to harvest the 5-in. wood, this would drop to $15 /m3 for the large wood. As co-author Brad Turner concluded, “at a recovery in the 280 to 300 bdft /m3 range, a difference in harvesting costs of $5/m3 equates to something in the order of $17 per Mbft lumber sold, so clearly nothing to sneeze at.”

Brad Turner is a principal with HALCO Software Systems Ltd. in Vancouver, B.C., and can be reached at 604-731-9311, ext.102, or by e-mail at bradt@halcosoftware.com. Scott Jamieson is the group publisher and former editor of Canadian Wood Products and can be reached at (519) 428-3471, or by e-mail @ sjamieson@annexweb.com.

Print this page