Features

Forestry Management

Harvesting

2021 update on forest certification in Canada

April 28, 2021 By Tony Rotherham

Canada is a global leader in forest certification. In 2020, I provided an update on Canada’s changing certification landscape. But how have things changed since last year?

The short answer is that the 2020 year-end statistics on certification in Canada show little change from 2019. The minor changes can be attributed to transfers of forest management areas from one forest management organization to another. The transfer may cause a ‘pause’ in the listing of the certification. Blame fires, mountain pine beetle and COVID-19, which have caused the closure of several sawmills.

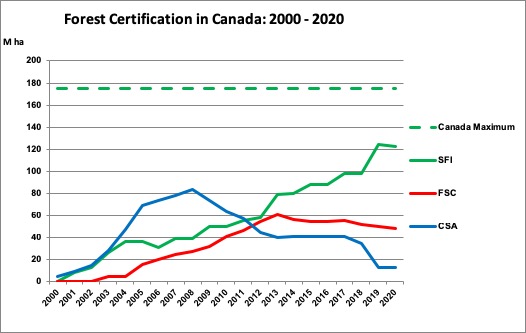

The total area certified to the requirements of the three certification programs used in Canada at the end of 2020 was 183.7 million hectares (ha). But there are about 20 million ha of forest that has been certified to Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) or the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) as well as to the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). This ‘double counting’ must be removed to get a true figure for the total area of forest certified in Canada. The total certified area with ‘double counting’ removed is 164.3 million ha.

The maximum area of forest likely to be certified in Canada is estimated to be 175 million ha. There will be some certification among the 450,000 private woodlots covering about 20 million ha but certification of small properties is complex and expensive – most woodlot owners do not harvest every year and are unlikely to get involved. The vast majority of larger blocks of forest, whether Crown Land Forests or large privately-owned forests, have been certified to one of the three certification programs used in Canada (CSA, FSC or SFI).

Internationally, forest certification continues to be a competition between the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) and FSC. Under PEFC, 324,587,605 ha have been certified to 40 national Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) standards that have been reviewed and endorsed by the PEFC. Both SFI and CSA are endorsed by PEFC. Under FSC, 223,707,812 ha have been certified.

New aspects of forest management

There are several interesting new aspects of forest management that are attracting public attention. The main one that may increasingly affect forest management and the marketing of forest products is forest carbon. Forests are recognized as stores of carbon. The tree absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere, builds the carbon into the wood, and emits oxygen back into the atmosphere.

If an area of forest under management is heavily harvested and the forest’s carbon content is reduced, there will be claims that management is not sustainable and is contributing to atmospheric carbon and climate change. Careful respect for Allowable Annual Cut limits should maintain the carbon content of the standing volume of forests and soils, but actual monitoring of the standing volume and rate of growth may be required to convince critics that all is well. This has not been part of SFM standards in the past, but perhaps could be considered.

It is important to note that the name of the certification program has nothing to do with forest carbon accounting. Forest carbon accounting will be based on a well-designed forest inventory and growth and yield program carried out at appropriate intervals. The faster the trees grow, the shorter the rotation and the interval between inventories. More attention to the genetic excellence of seed used to produce planting stock will be repaid in improved growth rates, resistance to disease, better form and wood quality.

There is a positive side to forest carbon – the carbon content of wood. A house built with wood contains a lot of carbon that has been sequestered from the atmosphere during the growth of the trees from which the lumber has been sawn. Build a house with wood and you store a lot of atmospheric carbon in the structure. This reduces atmospheric carbon dioxide and fights climate change.

This is particularly pertinent to the adoption of mass timber construction. It is a low-carbon alternative to traditional construction systems and materials. Builders and architects involved with mass timber construction are particularly concerned with sustainability and low carbon materials. Trees are good at carbon capture and storage.

As an example: Framing a 2000-square-foot house takes about 12,600 board feet of lumber. The usual conversion factor is that there are 424 board feet of lumber in a cubic metre of wood. If that lumber is SPF, it has a density of 0.37. A cubic metre of SPF contains carbon equivalent to the greenhouse gases (GHG) emitted during the combustion of 289 litres of gasoline. The 12,600 board feet of lumber in an average 2,000-square-foot house contains carbon equivalent to the GHG emitted during the combustion of 8,588 litres of gasoline. How far will that take you in a car that gets 40 miles per gallon? About 76,338 miles or 122,140 kilometres.

So, if we look after the carbon in our forests, we may get a marketing advantage from the long-term storage of carbon in lumber, because it is carbon capture and storage without the huge capital cost of a carbon extraction plant. Perhaps FPInnovations, the Canadian Wood Council and Forest Products Association of Canada should conduct a study to determine the actual volume in cubic metres of planed lumber and wood-based panels (OSB and plywood) in typical houses built in Canada and the U.S, and then calculate the carbon content and GHG equivalent. A well-researched figure can then be used in public information statements and to correct “fake news”.

The table below provides examples of the carbon in one cubic metre of wood of a variety of common species and its equivalent in GHG emitted when burning litres of gasoline.

What else is going on in the world of certification?

The revised 2021 SFI Standard is now being reviewed by PEFC. It includes several additions related to mitigation of Climate Change and risk of fire. SFI has also just announced that they will be working with experts in management of urban forests in the U.S. and Canada to develop a Standard for the Management of Urban and Community Forests.

Biodiversity, age class distribution and genetics are as important in the urban forest as they are in a large managed forest, but for somewhat different reasons, such as the high cost of removing large trees from an urban environment and the impact on house-lined streets when a majority of the trees die.

During the 1960-70s, many towns in Canada lost all their big American Elms to Dutch Elm disease. Taking these trees down cost a lot of money and stripped the town streets of shade and the ‘cathedral’ effect of the tall Elms. We are now experiencing a similar loss of urban trees to the Emerald Ash Borer. Wise managers of urban forests will want to reduce the impact of pests and disease. Species diversity and age-class management will help.

A management standard for urban forests may help by providing a management checklist and a way to ensure that it is followed.

Tony Rotherham (RPF B.C. and Ont. (ret’d)) has worked on woodlands operations in B.C., Ontario, Quebec, Kenya and Iran. He worked for the CPPA (now FPAC) in the Woodlands Section for 21 years and since then as a consultant, largely on private forest land policy.

Print this page