Industry News

Markets

Delivered lumber cost to US, competitiveness set to change

July 17, 2017 - The impact of duties on Canadian lumber exports to the U.S. will be a game-changer for different producing areas in North America, and also for exporters to the U.S. from overseas.

July 17, 2017 By Russ Taylor

Quite simply, punitive duties will need to raise the price of lumber in the U.S. to a point that allows Canadian lumber back into the market; alongside this will come increased imports from Europe.

Essentially, a new “floor price” will be established, with lower total imports (especially from Canada) and increased U.S. lumber production.

Background

The previous Softwood Lumber Agreement (SLA) ran from 2006 to 2015 and involved a lumber tax on Canadian exports at various price thresholds. When the Random Lengths Lumber Composite price was low (below US$315/mbf, nominal; US$197/m3, net), the export tax was 15 per cent on lumber exports from B.C. and Alberta, and a lower tax of five per cent (but in combination with a quota) was in place for the rest of Canada. When lumber prices increased to reach a higher threshold, lower taxes were paid, and, when prices finally reached US$355/mbf (US$222/m3, net) or higher, no export taxes were paid.

For a new SLA to be implemented, the U.S. is pushing to impose a volume-based quota that would limit annual, quarterly or monthly Canadian shipments to the U.S. In peak demand periods, a quota would hold back Canadian lumber exports and make excess volumes subject to very punitive penalties. Since Canada’s share of the U.S. softwood lumber market has averaged about 31 per cent from 1995–2015 (and 32 per cent in 2016), a one per cent change in quota is close to 500 mbf. Some initial U.S. proposals want the quota on Canada’s market share of U.S. consumption to drop to 22 per cent over a few years. A 22 per cent quota would imply a huge plunge in Canadian lumber imports to the U.S. of some five billion bf – 15 per cent of total Canadian production! This severe scenario makes little sense, as it opens up the question of where the U.S. will obtain its lumber from in the short-term. We estimate that the U.S. can produce only about 70 per cent of its own lumber demand, and, with Canada’s market share in the U.S. dropping further, the way is paved for an increase in imported lumber from Europe, Russia and other countries – and at higher prices. It seems that the objectives of the American side are clear: to raise lumber prices (and log prices) and create a windfall for U.S. sawmills and timberland owners, but with the consumer (and Canadian mills) paying for it.

US-Canada Lumber War

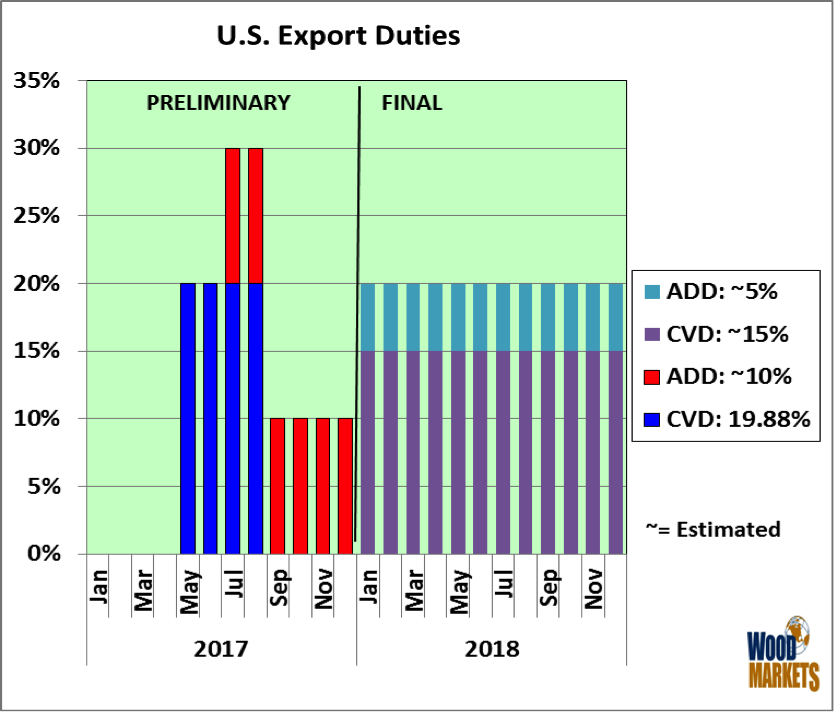

The announcement of preliminary countervailing duties (CVD) of 19.88 per cent on Canadian lumber shipments to the U.S. effective April 28, 2017 is applicable to all Canadian companies with the exception of five specific firms that receive rates ranging from three per cent to 24 per cent.

Along with the preliminary anti-dumping duty (“ADD,” expected to be around 10 per cent when it will be announced in late June), the combined duties will have significant impacts on delivered lumber costs for Canadian mills to the U.S. While the export duties will make U.S. lumber more competitive due to higher prices, it will also allow European lumber exporters to gain a significant competitive advantage when selling into the U.S. market. Since European sawlog costs are higher than those in North America, European exporters have required higher lumber prices to enter the U.S. market; the duties on Canadian lumber, coupled with a devalued euro, will accomplish just that.

The current softwood lumber trade dispute, known as “Lumber V,” is a continuation of previous U.S. concerns going back to 1980 – and “Lumber IV” (2001 to 2015). The root of the disagreement seems to be that 90 per cent of Canada’s timber harvest originates on Crown lands. The U.S., on the other hand, sold most of its timber long ago and today operates using mainly private forest land. The U.S. side claims that the pricing of Canadian timber is too low and, therefore, that the government is “subsidizing” its industry. In Lumber Wars I to IV, this could never be completely proven by the U.S. side, but American interests remain determined to make U.S. trade law work in such a way as to raise the price of lumber – and therefore the value of their private timberlands. The details of the case are complicated but, in short, the U.S. wants to place export duties on Canadian lumber because, well…because it can (under U.S. trade law).

While most estimates expect the combined, final duties in January 2018 to be 25 per cent–30 per cent, is it only a coincidence that the Canadian dollar has devalued by about 25 per cent since January 2013? It may be that the real issue of competitiveness is not related to government timber pricing at all, but simply to global foreign exchange rate changes (where almost every country in the world has seen its currency devalue relative to the U.S. dollar, thereby gaining competitiveness against it).

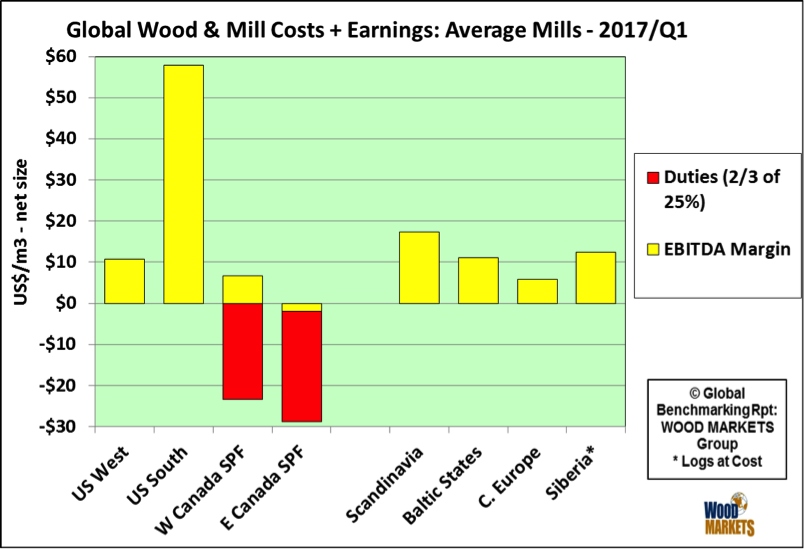

If there is indeed a “subsidy” as claimed by the U.S. side, it would seem the Canadian industry must be making huge sawmilling margins as compared to American mills. Well…no. We can state with certainty (as we have for many years via our Global Timber & Sawmill Cost Benchmarking Reports) that this is simply not the case. In fact, since 2008, the highest sawmilling margins in North America (often in the world) have been mills in the U.S. South – they averaged roughly 30 per cent EBITDA in Q1/2017. By contrast, the poorest-performing North American region since 2002 has been Eastern Canada (averaging 10 per cent to 15 per cent EBITDA in Q1/2017 before considering the 20 per cent CVDs). This begs the question: what claims could the U.S. South industry ever make with respect to Eastern Canada? Export duties of 25 per cent–30 per cent will marginalize Eastern Canada even more and further fatten the margins of U.S. South mills.

As we stated earlier, this issue is complicated; some aspects are frankly quite illogical. It seems that the heart of the matter may lie in the west, where the B.C. Interior’s industry is pitted against that of the U.S. West (mainly Washington and Oregon). These regions have tended to have somewhat similar operating results following the global financial crisis, but, starting in 2014 when the Canadian dollar began to devalue, the B.C. Interior has had better sawmill earnings than the U.S. West. This may be the true issue that has prevented any renewal of the previous SLA and triggered the start of a new lumber war. Again, however, it is complicated – and now very political!

Sawmill cost benchmarking

WOOD MARKETS latest timber and sawmill benchmarking report, Biannual Global Timber/Sawmill/Lumber Regional Cost & Revenue Profiles: Q1/2017, analyzes the delivered log and sawmilling costs and margins in major regions of North America, Europe and the Southern Hemisphere. The Q1/2017 analysis is based on data to late February 2017 for “average” structural lumber mills (excluding specialty mills; top-quartile or “best” mills have improved results). Aside from a 19.88 per cent export duty that commenced on April 28, 2017, retroactive duties have also been applied back to late January 2017. (Essentially, Canadian mills were forced to try to raise prices, selling lumber blindly without knowing the outcome of U.S. trade actions until 90 days later.)

For the analysis conducted, a 25 per cent export duty on Canadian mills was applied for the full quarter, where it is assumed that the market would absorb one-third of the duties (or a net duty of 16 per cent). This is a more pessimistic estimate than what actually happened in Q1/2017, as the U.S. market absorbed the bulk of the 19.88 per cent duty going all the way back to late January. However, this is not expected to be the case going forward: U.S. lumber prices continue to ease off their peaks of April 2017 (the highest lumber prices since early 2005) and were down 15 per cent in mid-June.

Based on the assumptions above for “average” sawmills, the results show that export duties marginalize mills in Eastern Canada: they would report a loss position under these circumstances (figure 1). Western Canadian mills would move close to a zero margin after duties. The duties allow U.S. West mills to finally achieve higher sawmilling margins than Canadian mills despite the region having the highest delivered log costs in North America (almost double those of the U.S. South, whose delivered log costs are only slightly higher than those of Canada’s SPF region).

The U.S. West faces a somewhat unique situation, as timberland owners are able to benefit from strong log export markets in China and Japan. This has placed rising pressure on the domestic sawlog supply and kept log prices high. At the same time, it has somewhat constrained lumber production and sawmill margins, since the U.S. West has the highest delivered log costs in North America. Throw in the 25 per cent devaluation of the Canadian dollar to the U.S. greenback and the U.S. West industry has been looking for a way out. This is notwithstanding the fact that the provinces of B.C. and Quebec have had long-term timber sale programs that tie government timber stumpage rates to market log prices.

For perspective, European sawmills have the highest delivered log costs in the world; this is particularly the case in Central Europe (Germany and Austria). Siberia, conversely, has the lowest delivered log costs (a result of the devalued ruble). However, log quality, diameter and logistics are key factors in European log costs, and it is the higher-quality logs in combination with log merchandizing that provide the lowest sawmilling costs. Of note, weaker overall market conditions, coupled with high total costs, have led to small sawmilling margins in Europe for the last five years or so. When the total costs of logs and sawmilling are combined (minus by-product revenues) in North America and Europe, the U.S. West still comes out with the highest total production costs; Siberia has the lowest. When net 16 per cent export duties are included, Eastern Canada has the second-highest total log and sawmilling costs and Western Canadian SPF mills become more on par with European mills.

In terms of sawmilling margins in Q1/2017, “average” sawmills in Eastern Canada would record a small earnings loss at a net 16 per cent export duty on U.S. lumber sales. Western Canadian “average” SPF mills would earn only a small margin – even less than their European counterparts. As a result, WOOD MARKETS is forecasting higher U.S. lumber prices (to keep Canadian mills in play) and this will allow European exporters to increase volumes to the U.S. This will especially evident in 2018 when the full brunt of the final export duties will land on Canadian mills.

Delivered lumber costs to U.S. South

The implementation of a 25 per cent (net 16 per cent) export duty on Canadian lumber essentially flattens the cost curve of competing regions and countries to the U.S. market; in fact, it is very effective at marginalizing Canadian lumber to the U.S. South region. When a delivered lumber cost analysis to the U.S. South (using Houston, Texas) was conducted (see our Biannual Regional Profiles Report • Q1/2017), it shows that, with a 25 per cent (net 16 per cent) Canadian export duty in effect, Canadian mills become high-cost suppliers to the region (like the U.S. West). Some of the lower cost suppliers to the U.S. market (after the U.S. South itself and the U.S. Inland region) become various European countries. Simply put, the high log costs in the U.S. West still maintain this region as a high-cost lumber supplier to the U.S. South – higher than European mills. The higher costs for Canadian mills will need to translate into loftier lumber prices, allowing European exporters to fill the gap left by Canada. Of course, all U.S. mills will benefit from this windfall of Canadian duties.

What is not factored into the analysis is that European mills’ costs could be even lower when producing for the U.S. market. This is predicated on the fact that producing dimension lumber or studs can provide some cost offsets, e.g.:

- An ability to use lower-cost logs, such as more pine and short logs (cheaper than profiled in the analysis);

- An ability to obtain longer production runs on dimension lumber or studs (lower sawmill costs); and

- An ability to obtain a higher lumber recovery from logs (i.e., allowing some wane).

On the other hand, Europeans would face some incremental costs or risks, including the following:

- Higher costs in operating planers (versus rough sawn production);

- Market price risks in selling six to eight weeks in advance to the U.S.; and

- Freight and foreign exchange risks.

The net result, as we are forecasting, will be higher U.S. lumber prices that will keep Canadian mills in play but also enable European exporters to expand the volumes they ship to the U.S. market. Already, European softwood lumber exports had increased by 400 per cent in the first four months of 2017 as compared to the same period in 2016. This trend will be especially noticeable in 2018, when the full brunt of the final export duties will fall on the shoulders of Canadian mills. It will be a bumpy road going forward, and price volatility will be increasingly evident.

Our most current analysis from 2016 to 2019 predicts some of the trends shown below in the U.S. market and North American industry.

U.S. demand conditions

- Both the U.S. and Canadian economies have surged forward.

- In the U.S., conditions supporting housing starts are strong: rising consumer confidence; high builder optimism; historically low interest rates; tight inventory levels of both new and existing for-sale housing; and an affordability index that is at a healthy 110 (meaning that a family with a median income can afford 110 per cent of a median-priced home).

- Furthermore, real wage growth, stuck just below two per cent from 2010–2015, has finally risen to a post-recession level of just over three per cent.

- After a long period of underbuilding and price recovery, U.S. housing starts are forecasted to grow by seven per cent per year in 2017 and 2018. This is good news.

- The eventual return of U.S. housing starts to their 50-year average of 1.44 million units per year is expected to occur around 2020.

- Currently, the homebuilding industry is being held back in its growth by shortages of housing lots, financing and labour, and also by high regulatory costs (adding as much as $20,000 to the cost of a new home). It is estimated that only some 40 per cent of the pre-recession construction labour force has returned to their jobs.

- While there is considerable pent-up demand, the percentage of first-time buyers in the market is creeping back to its historical average of 40 per cent – at just 32 per cent in 2015, it rose to 36 per cent in 2016.

- In a bid to attract first-time buyers (including the burgeoning millennial population), home builders are starting to offer more “entry-level” homes, such as D.R. Horton’s floor plans branded as “Express Homes.”

- U.S. lumber consumption is forecasted to rise over the next few years, from an expected level of 49.6 billion bf in 2017 to a forecasted 55 billion bf in 2019 (+11 per cent in two years; five to seven per cent per year). Much of this increase will need to come from U.S. sources or offshore imports, as Canadian production is expected to decline slightly from 2018 onward (due largely to additional mountain pine beetle-related closures in the B.C. Interior as well as curtailments from low net U.S. sawnwood prices).

- In contrast to U.S. housing markets, Canadian markets have been overbuilding relative to demographic trends. Canadian housing starts are currently projected at a buoyant 202,000 for 2017, then easing to 182,000 in 2018.

- In 2016, Canada accounted for roughly 15 per cent of the 55.7 billion bf of softwood lumber consumed in North America.

- U.S. supply trends

- On the supply side, the expected timing of the preliminary and final duties will have a dramatic impact on softwood lumber prices as well as Canadian and U.S. production.

- Total duties, starting with the preliminary CVD – now at 19.88 per cent – will rise in July as a preliminary ADD is added in. The duty levels will then fall in September as the preliminary CVD expires, and then ultimately rise again in January 2018 when the final CVD and ADD rates come into effect (figure 2).

- U.S. lumber production is indeed growing, but each producing region faces its own challenges. In the U.S. South, sawmill capacity has not increased as fast as timberland volumes. The ensuing, massive excess inventory “on the stump” has kept log prices down even as lumber prices have risen, resulting in higher margins for lumber producers.

- While sawmillers have been investing in expanding their existing mills, a shortage of skilled labour in the U.S. South region has limited greenfield mill capacity expansions.

- The story is slightly different in the U.S. West. Here, production has also been recovering from pre-recession levels, but growth has slowed in the last two years. As in the U.S. South, much of the log supply available to western mills comes from private forests. However, strong purchasing competition from Chinese mills has pushed up log prices, squeezing sawmill margins.

- We expect increases in U.S. lumber output, especially in the U.S. South (where timber is plentiful and cheap).

- While pine sawlog prices in the U.S. South have trended down over the past decade, U.S. West prices for both whitewood and Douglas-fir sawlogs have risen. For example, March 2017 prices for #2 whitewood and Douglas-fir sawlogs were $535/mbf (Scribner scale) and $658/mbf, respectively, in contrast to $178/mbf for southern pine sawlogs.

- With new export duties (estimated at a total of 20 to 30 per cent), Canadian exports to the U.S. are expected to drop by 10 to 15 per cent in 2018 from 2016, or a decline of about 1.5 to 2.0 billion bf (2.3 to 3.2 million m3).

- 2018 could be a tough year for higher-cost Canadian mills, as the full bite of U.S. duties will be in effect and may lead to numerous curtailments across the country.

- By 2019 the U.S. will need more Canadian lumber, so we anticipate that higher prices will begin to allow curtailed mills to restart.

- The U.S. will need rising imports – if not from Canada, then from Europe and the Southern Hemisphere – and this means high prices for both logs and lumber.

Russ Taylor is the president of International WOOD MARKETS Group based in Vancouver. International WOOD MARKETS Group Inc. is a wood products consulting firm. The company provides market research, new business development, business plan/strategy, and other consultative services to wood products companies in North America and around the world. www.woodmarkets.com

Print this page