Features

Features

Women in Forestry

Inclusive safety: Addressing PPE challenges for women in forestry

Many women in forestry struggle to find personal protective equipment that fits appropriately and works for them. CFI spoke with women in the industry to learn about their experiences, what can be done to address the issue, and the potential impact this could have on the industry as a whole.

April 5, 2022 By Ellen Cools

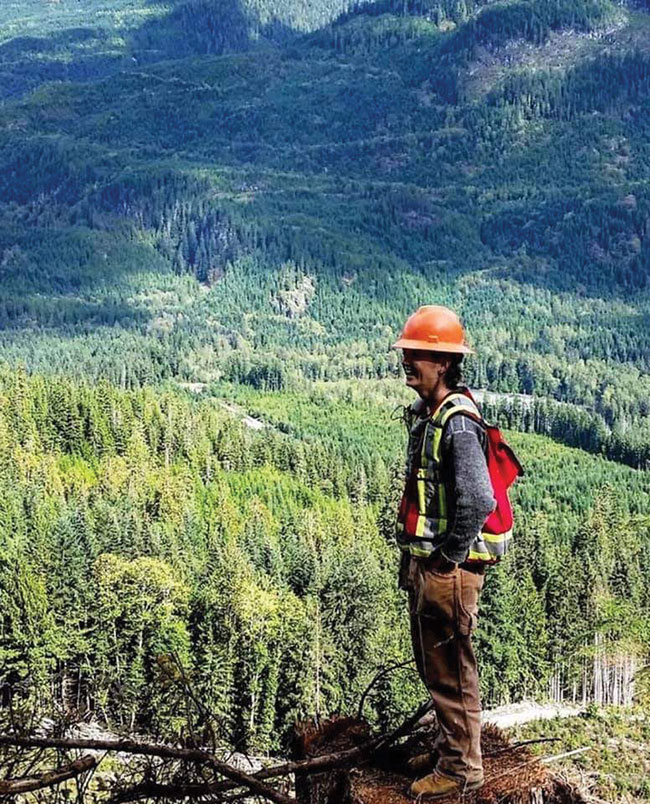

Many women like silviculture forester Kaitlin Conroy have struggled to find personal protective gear that fits and works for them. Photos courtesy Kaitlin Conroy.

Many women like silviculture forester Kaitlin Conroy have struggled to find personal protective gear that fits and works for them. Photos courtesy Kaitlin Conroy. Canada’s forest industry has historically been dominated by white males. In fact, in 2016, women made up just 17 per cent of the forestry workforce. But, the industry has been working to change this statistic, addressing the problem of gender inequity through different projects including the #TakeYourPlace campaign, the Free to Grow in Forestry online information portal, and CFI’s Women in Forestry series and Women in Forestry Virtual Summit.

These initiatives have brought more attention to the career opportunities available to women in forestry and helped address diversity, equity and inclusion in the industry. But, a lot of work still needs to be done to ensure the sector becomes more inclusive and equitable. And there’s one issue that has often been overlooked – one that could help to attract and retain women in the workforce: more inclusive personal protective equipment (PPE).

Many women in the industry have struggled to find PPE that fits appropriately and works for them. Most of the gear that companies supply is in men’s sizes, and women have had to put up with ill-fitting vests and pants, and find workarounds for gear like boots and hard hats.

CFI spoke with a few women in the industry to learn more about their experiences with PPE, what can be done to address the issue, and the potential impact this could have on the industry as a whole.

One size does not fit all

“Generally, all of the PPE offered in forestry is for men, not even co-ed. I’ve really never been exposed to anything specifically made for women. So, the struggles are very real,” Kaitlin Conroy, RFT, silviculture forester with Canoe Forest Products, says.

Conroy got her start in the industry tree planting back in 2008, and has held multiple silviculture roles for different companies over the years. Conroy is 5’7” and 125 lbs., which means that, while her height makes it easier for her to wear men’s clothing, the waist size does not work.

“Having loose clothing, especially when it’s your PPE, is not ideal,” she says. “Even chainsaw-cutter pants – which I’ve had to wear for work as a brusher – those were difficult to find in a small size, and once I found them, the waist belt was fully cinched all the time.

“Men and women’s body types are quite different, so it doesn’t work to take a size small men’s all the time,” she adds.

Andrea Robinson, who has also worked in the forest as a harvest technician and firefighter, has also had trouble with gear supplied by her previous employers.

“A lot of supplied clothing generally doesn’t fit,” she says. “I’ve experienced that with high-vis. It’s a one-size-fits-all model, which doesn’t even work for men – so, why they think it’s inclusive and is going to work for women as well, I’m not sure.

“It can be a safety hazard if your supposedly safe clothing is dangling around while you’re doing something that requires skill,” Robinson says.

Conroy agrees, explaining that she has to wear a size small red cruiser vest that’s too large for her. As a result, the waist of the vest sits below her hips, which puts additional strain on her shoulders.

Nicole Galambos, wildfire training manager, director for the Hinton, Alta., training centre, and chair of the Diversity and Inclusion Working Group for the forestry division with the government of Alberta, also points out that chest packs and high-vis vests are not appropriate for women because the breast pocket is over the chest and many women cannot put their radio in that pocket.

Women in the industry also often have a difficult time finding hard hats and boots that fit appropriately. For Robinson, hard hats do not run small enough, so she has to put her hair into a bun and tuck it into the hat to keep it from falling off.

“I’ll do danger tree assessments and things like that where you have to be looking up constantly and my hard hat literally falls off. So, it’s not very useful at the end of the day, if it’s just going to do that,” she says.

With regards to work boots or steel-toed boots, often they do not run small enough or narrow enough to fit women properly.

“I have really skinny feet and narrow heels, and I had to get my last ones essentially custom-made because the ones that are supposedly the best just don’t fit me,” Robinson says. “People who work in the bush know that having healthy feet is one of the most important things, especially if you’re going to be out and about for 12 hours a day in the muck, you have to have good boots.”

Kaitlin Conroy got her start in the industry tree planting in 2008, and has held multiple silviculture roles for different companies over the years.

A lack of awareness?

Despite the difficulties that women in the industry face as a result of ill-fitting PPE, there has been limited dialogue within the sector about the issue. Most of the discussions are among women in the industry; for example, many women who are part of the Women in Wood networking group on Facebook have discussed the challenges they face and shared the workarounds they have found.

“If you’re a female, you understand this is an issue, but I’m not sure it’s broadly understood how challenging it is,” Galambos says. “Certainly, when I chatted about it with my management team, it seemed like it’s news. If it’s not a problem for you and no one’s bringing it up as a problem, then how would you know it’s an issue?”

Part of the reason why there has been limited discussion on the issue is because women are still a minority in the industry, Galambos and Conroy say. According to the Association of B.C. Professional Foresters, in 2021, just 22.3 per cent of the professional foresters in the province were women.

“From my personal experience, I know a lot of those women aren’t necessarily even field workers. They have more of an administration-style role,” Conroy says. “So, I think the problem is that people are aware, but there’s not enough of us to cause a stink.”

As such, there are not many suppliers that are focused on bringing women-specific forestry gear to the market.

“I’ve seen a few ads here and there, or someone will say they’ve heard a company is doing something, but in general, I don’t think it’s widely accessible at all,” Robinson says.

Robinson says equipment manufacturers need to provide more variety in sizing, but adds that it should not necessarily be advertised as women’s sizing, given that there are people of all genders in the forest industry.

“By having the distinction between men’s and women’s, I feel like it doesn’t totally hit the inclusivity mark. If they just offer a proper variety of sizes for everyone, then I think that would help a little bit more,” she says.

Most PPE offered in the forest industry is designed for men, which can have safety implications for women.

‘A step in the right direction’

As more women and people of other genders join the industry, some companies are starting to provide more inclusive PPE. One such company is Zomboots, which sells caulk boots for women.

Caroline Smith, the owner of the company, was a tree planter and found the caulk boots she had to wear were a safety hazard.

“I found the ankle support was so bad and the boots were really heavy, so I felt like I was twisting my ankles every day. I was angry that I didn’t have proper fitting boots, so I decided to try to start making them,” she says.

And the response to Zomboots has been very positive.

“Most of the emails I get from people, they’re so thankful. They’re thanking me and they’re so excited to have boots that fit. They just seem happy that somebody has finally taken the jump to make them,” she says.

Smith is not alone in taking the plunge and starting her own company to provide PPE for women. Another woman, Audrey Rippingale, decided to start her own business called She Works, She Plays. Rippingale drives a trailer around B.C., bringing work and outerwear to women who work in the resource industries, such as mining and forestry.

According to Galambos, a few other companies are beginning to provide gear that is more appropriate for women. Coaxsher is providing a Nomex pant designed for women, and True North Wildland has a Nomex shirt for women.

“For the shirt, they’ve taken the breast pockets and moved them down lower so you can actually make use of them, instead of trying to use the pockets on your chest, which is not something a lot of women are comfortable doing when that space is already occupied,” Galambos explains.

With more women and people of other genders in the forest industry, Galambos believes suppliers will see there is a growing market for more inclusive PPE.

“That’s certainly what we’re starting to see in wildfire – more and more females coming in at all levels in the organization, and I suspect that’s how private industry works,” she says. “I love that there are options coming onto the market. We have a long way to go, but it’s a step in the right direction.”

Improving retention

And having more inclusive and appropriate PPE for people of all genders could help address forestry’s ongoing labour shortage.

“How could it not?” Galambos asks. “Personally, there’s no way that [the ill-fitting gear] is not impacting my ability to feel confident and comfortable, and to perform my best.”

Robinson agrees, saying that having appropriate PPE would not only help retain but also attract women and people of all genders.

“Some people who are really small are intimidated by the fact that they might not be able to fit into the gear or they look really funny in it. There’s a fear of portrayal of that in this male-dominated workforce,” she says. “You might like your job a lot, but at the end of the day, if you’re not feeling comfortable or safe, it’s not really worth it for some people.”

Conroy adds that it could encourage more women to see fieldwork as a possible career choice. “Maybe it’s not even in their thought process at this time because they never see a woman fully decked out in PPE that fits.

“It would be really nice to have the proper gear that fits,” she adds. “It’s a tough go out there – conditions, Mother Nature – so the last thing you want to be fighting with is your gear. The gear is supposed to protect us.”

Print this page