Features

Operation Reports

Remanufacturing

Thinking Outside the Box

A pallet stock remanufacturer is proving that you don’t need the latest and greatest technology to survive today’s market crunch, just razor-sharp marketing skills and a willingness to think outside the box when chasing non-traditional export markets.

November 30, 2011 By Jean Sorensen

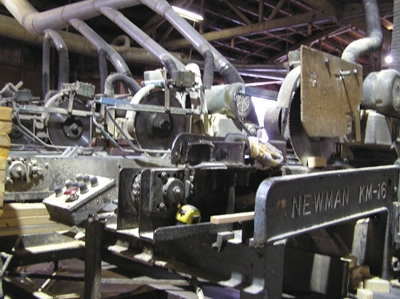

A Newman trim saw was one of the first pieces of equipment the Amir brothers installed in their remanufacturing plant. A pallet stock remanufacturer is proving that you don’t need the latest and greatest technology to survive today’s market crunch

A Newman trim saw was one of the first pieces of equipment the Amir brothers installed in their remanufacturing plant. A pallet stock remanufacturer is proving that you don’t need the latest and greatest technology to survive today’s market crunch

It is this type of ingenuity that has earned Port Moody, B.C.-based SPF Precut Lumber and its owners, the Amir brothers, B.C.’s 2008 Exporter of the Year Award, an honour earned with a lot of early mornings, creative thinking, and weeks spent on the road in foreign countries seeking out buyers.

As company president Mohammad Amir walks through his 40-year-old leased Port Moody building, a former radio manufacturing facility that’s seen better days, a wall of pallet stock seemingly disappears into the horizon. “This is all going to Saudi Arabia,” he says, explaining that the oil-rich country is also gushing up new manufacturing capacity, both to meet its local needs and those of the export market.

Saudi Arabia once tallied up to 97 per cent of its exports from petroleum. In 2005, the Saudi Fund for Export allocated SR 15 billion (about $5 billion Canadian) to underwrite credit facilities, encouraging exports to more than 30 countries of non-oil related manufactured products in areas such as petrochemicals, plastics, agricultural equipment, construction products and food products. For savvy opportunists like the Amir brothers, it translated into the country needing more shipping pallets.

The Amir brothers reman plant rips kiln-dried lumber (No. 3 and economy grade) into pallet stock in varying sizes and ships it to Saudi Arabia receiving plants, where the finished product is processed. Today, the Amir’s Port Moody plant, which is in suburban Vancouver, is considered the largest producer of pallet stock in Western Canada. Annually, 110,000 cubic metres of pallet stock rolls out of the yard. The five sizes range from 1x4x30-82 through to notched 2x4x36-80 and are derived from 2x4s, 2x6s, 2x8s, 2x10s and 2x12s.

But, Saudi Arabia is just one of many off-the-beaten-track markets that Amir, with younger brother Fareed has gone after. Other Middle East markets include Dubai, Katar, Jordan, Israel and Kuwait. Fareed just returned from a trip to Pakistan, and now he’s heading off to the Far East, hitting countries such as Vietnam. China is another hit-list country where the Amir brothers are well known. Currently, Mohammad says production is split almost 50-50 between the Far and Middle Eastern countries.

The Amir brothers’ formula is basic. One is on the road finding new customers and meeting with established ones, while the other runs the home show and shops for the timber supply needed to fill incoming orders. The company does more than just pallet stock and has been successful in finding smaller manufacturers searching for good quality, on-grade lumber from Canada. It ships approximately 100,000 cubic metres of Canadian dimensional kiln dried lumber to markets that include joineries, cable-reel manufacturers, prefabricated home manufactures, door-frame manufacturers, furniture manufacturers, and the construction and packaging industries in the Middle East, Far East and Southeast Asia. These are all niche markets that Fareed has uncovered while on the road.

The Port Moody yard is massed with approximately 12,000 cubic metres of incoming wood from major suppliers, but Mohammad is also on the phone looking for specialty cuts needed for niche foreign customers. When times are good, the company employs 30 people in the office and plant. Currently, the staff numbers have been reduced by half. But, despite a tougher market, four or five container trucks continue to roll out of the yard every day.

For Mohammad, shutting down the mill would not be an option. He’s struggled too hard to get where he is and believes, “there’s always a customer out there, it’s just a matter of finding them.”

Rain, snow, sleet or sun, Mohammad rises just after 4 a.m. every day and arrives at the plant by 5:30 a.m. “My brother works the same hours,” he says. By 6:30 a.m., the mill is operating and runs l0 hours per day, five days a week, realizing a 50-hour workweek. “Everyone gets paid extra for that,” says Mohammad, as employees put in what amounts to an extra week’s production every month.

Getting Started

The family history is the typical Canadian immigrant story with the Amir Brothers coming from Pakistan. Mohammad had worked for many years in the shipping business, and had spent time working in Saudi Arabia’s ports. He arrived in Canada in 1989, realizing there were, “few industries where I could make a good living,” narrowing his choices down to either real estate or the lumber industry.

His background in shipping dovetailed best with the forest industry and he sent out applications to 170 companies in three months. “Selling is really a numbers game,” he says, adding that enough resumes eventually landed a position with Kuehne & Nagel, one of the world’s largest forwarders.

By 1990, he felt he needed to do more so he set up a small business with his wife in their basement suite and began selling lumber into a market that he knew – the Middle East. He was fortunate to represent some of the larger names in the business and his client list grew. He noticed an international demand for more pallet stock and in 1996 he set out to operate a reman plant. He knew nothing about equipment or running a plant, but, with research, a good business plan and the support of the Business Development Bank, he launched the business with his wife and Fareed.

They bought a used dust collector, a Newman KM16 trimmer and an older-model band saw. A millwright put the equipment together and the trio began rustling up orders, mainly for the U.S. market. This is where Mohammad found he could further use his shipping expertise. There was a high cost factor in shipping lumber from the B.C. Interior, re-manufacturing that lumber in-house and then finding a truck to take the products south. Mohammed looked at the costs and came up with a different scenario. It made more sense to subcontract overflow orders closer to the wood source – such as pallet stock remanners in Williams Lake, Quesnel, and Vanderhoof. He found that dry goods were typically trucked into northern B.C. in containers and often the same containers were shipped back empty. Pallet material in bundles was clean and fit easily into containers so it became an easy decision and one that worked well. By 2001-2002, he was shipping out 15 container loads a day. “We took over the market,” he says, adding that even a slim profit of $50 to $70 a load on at least 600-700 loads a month provided a fairly good return. Business continued to grow until the U.S. market began weakening and finally crashed.

The Amir brothers have not suffered as much as others through this downturn. About four years ago, Mohammad looked at diversification and stumbled over news items such as the one about Saudi Arabia wanting to expand exports. “The demand went crazy for things such as prefab housing and pallet stock,” he says. These wood-starved Middle Eastern countries were also markets that the Amir brothers were familiar with.

The real question became how to get the material to the market at a competitive price against suppliers such as those in the Scandinavian countries? Again, Mohammed drew upon his shipping expertise noting that most shipments from B.C. go by bulk carriers rather than containers. He estimated that l0 container vessels were looking for back haul shipments compared to every available bulk carrier. The container became a cheaper solution, and again, it became an exercise in thinking outside the box. “That is what has made it interesting to us,” tells Mohammad.

Simple Strategy

Today, he still uses that simple strategy – where can he ship to at a reasonable price? That’s the foundation of making a deal work or sending Fareed to an area on a sales mission. He also believes in not just networking, but establishing solid customer relationships by having the language skills, and knowing the local customs and ways of doing business. That includes having Asian-speaking personnel in the sales office.

Now with nearly two decades of expertise behind him, he’s able to set out what he thinks are the keys to success in finding niche foreign markets. “You need to know the customer’s product – this is most important,” he says. “Then, you should be able to source the wood at the most economic level. And, finally, stick to the deal,” he stresses. “If you provide a price for a customer and then you can’t deliver, you can’t go back and change it,” he explains. “That’s something that often happens in the marketplace today and it erodes customer loyalty.”

He believes it’s better to take a loss than lose the confidence of the customer. “The pay-off in export sales is over the long-term relationship,” he maintains.

Print this page